The Fear of Change

Rosanne Cash

Whether we experience it individually or within human constructs (religion, organisations, families, clubs, etc), there is a Fear of Change ingrained in us in both business and personal life. Humans are comfort-creatures; we value stability and comfort in our lives, be it professionally or at home. So what happens when the ever-changing Universe rudely reminds us that everything is, ultimately, transient?

It is very human to deny that change is happening, that a system has become (or always was!) un-ordered. The reaction is often to then try to impose order (constraints), and often we do this to systems or situations that cannot by nature be ordered.

Change represents the oft-acknowledged deepest fear of mankind: that of the unknown. We know we are here, and find comfort, even in uncomfortable situations; true change will really change things, and this can induce anxiety, worry, discomfort, fear – not only of the consequences, but the change itself.

If something isn’t working, it needs to change for it to begin working. Sometimes the fear of change is so great that we would rather it simply continue not to work, because at least then we know it isn’t working; in other words, we have some form of certainty. This, of course, isn’t helpful in the long term, for delivering value, or in urgent situations, and to accurately gauge this we also need to understand the benefits or risks of making the change.

But what if something is already working?

One response is: why change if it works? (which can also mean, if it sort of works well enough, maybe, also I don’t want to spend money).

Why indeed? But as with everything, this isn’t a black and white situation, much as we love to polarise. It may be barely working, or require workarounds to complete. It may be inefficient or cause rising/unnecessary costs, or added complication and hassle to daily life. If it works well enough, which is highly subjective, you have to ask if it is worth changing. If the benefits of change are outweighed by the risks or clear negatives, or it is poorly perceived or understood, it is probably not worth doing.

But if you take any organisation with working processes in place, the chances are high that people will usually say, “Yes, it works, sort of – but it could work much better” about many of them, and then specify where the inefficiencies impact their overall effectiveness and workload. (A problem I have often found is that, where an organisation does undertake to make changes – be it a new system, process, or team – it is usually a higher-level decision that often doesn’t fully provide training, positioning, and applicable usage to the people actually doing the job, and can be either too simplistic, over-complicated, or ill-applied – in other words, not appropriate to resolving the core issue. This is why listening to the people doing it matters).

If this is the case, and benefits clearly outweigh risks… why not change it to make it work better?

The place to start with processes, change and the fear of that change is the same: you start with the people.

Why start there?

All processes, all base decisions, and all value delivered stems from the people within an organisation. People are interconnected individuals working within an organisational structure towards a common set of goals in a variety of ways; without those people – and their interconnections – the innovation, the products, the organisation itself would not exist.

Another way to say this is that people both create and are the value delivered by an organisation. Or, to put it in a more succinct fashion, Value Streams are made of People (Keogh).

So, recognising that the value of your organisation is the people is an important step, for a number of reasons. It is people who fear change, not the products or the infrastructure within an organisation; it is people who make an organisation work.

People fear the change wrought in any organisation because it disrupts processes and workarounds that may work imperfectly but still more or less work, and allow at least some value delivery. Worse, it may cause further inefficiency and unnecessary stress, or expose workarounds that are not strictly in line with company policy – but bureaucracy may have left them no other choice to achieve their business goals, which brings potential personal risk into play even in a clearly failing scenario.

“It works well enough.” “Let sleeping dogs lie”. “Don’t rock the boat.” “Don’t stick your head above the rest.” “Don’t stick your neck out.” “Don’t be sales/delivery prevention.”

These are human qualifications of not wanting to cause further potential problems, and become progressively more fearful of being singled out for causing issues, even if the root aim is to resolve perhaps more fundamental issues within the organisation to provide better, smoother value streams. Politics, bureaucracy, interdependency and tradition can all turn what looks on the surface to be a simple change into a highly complex situation and possibly render a goal unattainable, even though it may be to the greater good of the organisation. In a perfect world, a flexible and reactive enough organisation – one that recognises itself as a complex system overall – shouldn’t need covert workarounds; experimentation should be built in.

A root of this fear lies in uncertainty. People require certainty to maintain stability, comfort, and (relatively!) low stress. Knowing a situation is good or bad is far preferable to not knowing if it is good or bad or even what it is, so the natural inclination is to maintain the status quo and not be singled out, as long as this isn’t disruptive enough to become worse than the potential uncertainty (there is a fantastic example of the effects of uncertainty in a study involving rocks and snakes used by Liz Keogh in her talks).

Why do organisations not recognise this?

Some do, of course, but not many seem to fully realise the causes behind it. One of the most important things to understand is that the landscape has shifted and is shifting in modern business, even recently. Knowledge has become the primary global economy, with business being undertaken around the world, around the clock, and data being digitised and made available and changeable at exponentially greater quantities and speeds than ever before.

The management of this knowledge and the methods used have become key to an organisation’s productivity, innovation, and agility (Snowden, Stanbridge). Sprawling bureaucracies have given way to entrepreneurial practices, and many companies are caught between the two, trying to apply often contradictory methodologies of both to their staff and their products.

At the same time, the latest and not yet widely-understood shift to virtual systems, the increasing use of AI, and knowledge digitisation has moved business to a realm we have no prior experience of or reference for, and this causes fear and concern because we are being forced to change at both a personal and industrial level. Organisations push back against this by acting as they always have, cutting costs, replacing management teams constantly, and so on, but the simple procedures that once worked do not produce new benefits past the very short-term now.

This is because, without realising it, we are now experiencing the Fourth Industrial Revolution (Kirk), which is an entirely new landscape requiring new understanding and actions. Because organisations do not have either, many of them currently “feel like they are in Hell” as a result of the Dark Triad (Kirk):

• Stress

• Fatigue

• Antagonism (“Arseholeness!”)

…and they occur both at an organisational and a personal level.

One of the key reasons for these responses may be because of the still-existing and long-term investment in structures based in Taylorism (which dates back to the 19th century, yet is still a core of today’s management science), a root of Process Engineering. This can be interpreted as the belief and (and action upon the belief) that an organisation is a machine with people as cogs or components that will consistently deliver the exact same output in quality and quantity – or, that an organisation is both inherently ordered and conforms exactly to rules.

|

(Un-ordered)

|

MATHEMATICAL COMPLEXITY

|

SOCIAL COMPLEXITY

|

|

(Ordered)

|

PROCESS ENGINEERING

|

SYSTEMS THINKING

|

|

|

(Rule-based)

|

(Heuristic-based)

|

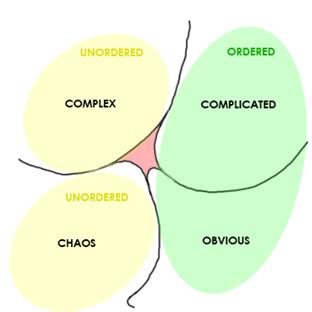

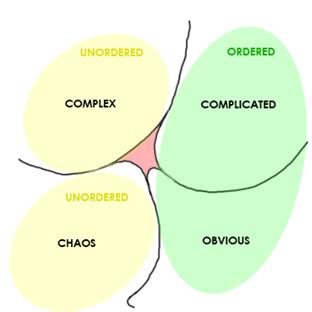

Cynefin Knowledge Management Matrix (Cognitive Edge)

Despite the realisation for decades that Taylorism is actually detrimental, because that just isn’t how people work, and supposedly eschewing it in favour of a more Systems Thinking approach (or, where an organisation is ordered, with greater flexibility from using heuristics) and a shift from a perception of “machine” to “human” (Peters, Senge, Nonaka), businesses have really only changed it slightly.

There has been a concerted effort to balance the Mintzberg et al Process Engineering-centric Schools of Strategy (Designing, Planning, Positioning), and the Systems Thinking-centric Schools (Entrepreneurial, Cognitive, Learning, Power, Cultural, Environmental, Configuration), but in my own experience of companies, especially some US-based organisations, I have still found a far greater leaning to the Process Engineering side with some nods towards System Thinking, and a greater perception towards an organisation being a machine, not people. In other words, here we try to force an organisation to fit the modified concepts of Taylorism because it is trusted and traditional, despite being proven ineffective, and act as if it will forever output the exact same quality and quantity.

Of course, even the most balanced approach here between the two still treats an organisation as an ordered construct with a variable spectrum of rules and heuristics, but the very presence of humans who can vary output, focus, workloads and innovation both within and driving an organisation dependent on a number of factors that aren’t necessarily causal or logical – that is to say, complexity – means an organisation can’t be a rigidly ordered system. It is by nature complex, un-ordered, but the tools we mostly use to resolve issues are based on it being an ordered structure with simple rules. The understandable preference, based on certainty and comfort, is to seek simplistic identically-repeatable approaches (“recipes”) based on clear and idealistic outcomes (Snowden).

Ontologies in relation to basic Domains (Cynefin)

What’s interesting is that people will try to manage an organisation as ordered when it isn’t, yet adapt very quickly to managing home life which is similarly un-ordered, often within the same day! This brings into focus the concept of our different identities, or aspects we transition between seamlessly to fit into different situations.

It is also very easy to miss that many instances can be multi-ontological. As a very simple example, if I run a technical training lab, I deal with an obvious domain in much of the basic subject, but also complicated areas; the systems I use to train are largely complicated; and the addition of students themselves bring complexity, as the students drive the class and every class is different to any before as a result (it’s rare that a class descends into chaos, but it’s not unknown, and usually requires outside influence!). So I can end up dealing with all three ontologies in one course! Order, un-ordered complexity, and un-ordered chaos all require different management, but they can all be managed (I touched on some of this briefly in my last blog post: https://www.involvemetraining.com/best-practices-vs-heuristics-in-teaching/).

The visible effects

By not changing from primarily Process Engineering thought structures for 50+ years of business practice, and many organisations not fully comprehending that the shift of many markets from product to service requires organisational agility (as a core concept, not a modular application!), markets are seeing the stifling of innovation and a downwards dive of productivity (Snowden).

This inevitably sparks a frantic reaction (change of focus, sudden arbitrary swerves to “disrupt the market” without recognition of opportunity outside a narrowly focused goal, cost cutting, redundancies, management team swap-outs, further cash injections, etc) without looking at what is working, and more importantly understanding that this is not a one-fits-all recipe that can merely be transplanted inter-organisation for success (Snowden).

It is becoming clearer that collaborative competitiveness, reactive approaches, SME level agility and innovation are where markets now grow in this new landscape of people being and delivering value via a knowledge economy, and this is a beneficial realisation for organisations struggling “in Hell” to take a first step into new understanding.

So what now?

“…Where we go from there is a choice I leave up to you…”

The more I look at the current struggles to achieve the results of yesteryear, my own experiences of the last twenty years plus, and the new evidence of Industry 4.0 (Kirk), the more I realise how accurate the above is. Interdependency and collaboration is clearly now essential in a new, barely understood industry of High Demand/Ambiguity/Complexity/Relentless Pace (Kirk). We haven’t been here before.

To find balance and prosperity, and deliver real value once more, collaboration, agility of approach and innovation are all required. We need to sense-make; we need to path-find, or forge our own new paths.

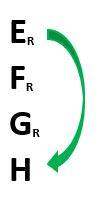

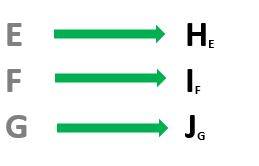

“Reacting by “re-acting”, or repeating our actions, merely causes problems to perpetuate. In a new landscape, a new reaction is required for change” (Kirk). This is also one of the keys to Cynefin and managing complex situations; it is virtually impossible to close the gap between the current situation and a goal when dealing with complexity, a system with only some constraints where each aspect affects all others. Instead, you must see where you can make a change, see where you can monitor that change in real-time, and recognise the opportunities to amplify success and ignore failure when it arises via experimentation (Snowden). Or: instead of trying to achieve an idealistic goal impossible from your current standpoint, instead make changes to the system that may throw up even better goals, watch for them instead of focusing on the old goal exclusively, and then grasp them when they arise. You must start from somewhere, but the key is to start – a certain step is the first one to conquering uncertainty.

“Organisations and people ALL matter, because they drive, innovate and ARE value; we matter because everyone else matters” (Kirk), and industry becomes, not forced into trying to be a destined-to-fail machine system, but a safe-to-fail ecosystem – holistic and interconnected, not only able to adapt to change, but driven by it.

The problems we still face

The issue in many organisations, and with many managers, is that it is very easy to believe correlation = causation, and that simple universally-applicable recipes give idealistic outcomes. This leads to problems, and is a driver of the industry “waves” of best practice management fads that don’t work long-term but propagate because they are new, and short or medium term results may have been seen by some other organisations.

What works to fix or improve one organisation is not necessarily (in fact very unlikely) to work perfectly for other organisations, or work subject to simplification and/for general application. This is a core concept still used that conforms to the Process Engineering ideology. You cannot take something in complex situations and reduce it to a repeatable generic recipe that works perfectly; it just… won’t. No two organisations are alike. Every instance should be approached, investigated, and worked on individually and holistically to see if it should be managed as ordered, or un-ordered (complex or chaotic). There is benefit from seeing what other organisations did to resolve similar problems as long as it is understood the approach and fit must be modified: the incorporation of aspects, rather than the dogmatic following of a whole.

Furthermore, the more people find approaches to be effective, the more they seek to codify the concepts – which is fine to a point, but can easily lead to them then structuring the approaches, modularising them, and then seeking to force them back into the ordered ontology (the Cynefin domains of Obviousness or Complication) as a simple, universally repeatable recipe, when many are ultimately agile and flexible tools to manage un-ordered systems (Complexity or Chaos). This is something that appears to be happening to the concept of Agile at the moment; it is becoming less agile itself as it is taken in by large organisations and constrained!

At the same time, there are constant clashes intra-organisation. Organisations want to both be fully ordered with infinitely repeatable output, but also flexible and innovative. The first of these is causal (repeatable cause and effect), and the second is dispositional (you can say where you are and where you may end up, even simulate, but not causally repeat or predict). They are very different in nature. By their very nature and composition, an organisation cannot be a simple ordered system, and this is where the work within Cynefin by Dave Snowden into Social Complexity/Anthro-Complexity begins to make sense of these systems and the management of complexity and chaos.

There is also the requirement for a deeper comprehension of the fuzzy liminality of whether or not you should make a change, which differs in each situation; a risk/benefit exercise where we weigh up the benefits – deep and long term as well as short term – of making a change, where the former is often ignored in favour of short-term profitability. Where the dangers of making a change are not defined or understood, or are clearly not beneficial, it is wise to consider carefully whether you should do so – and if so, what the correct manner of doing so is.

From Hierarchy to Ecology

One of the fundamental movements that resolves some of these issues I think will be a shift from Hierarchies, where organisations are ranked internally relative to status and authority with a focus on control (power), to Ecologies, where organisations recognise the relationships of every person to each other and to the organisation, with a focus on delivery (value).

This may then acknowledge change and the driving by change, and that organisations are largely complex and cannot be distilled into simple recipes repeatable for idealistic outcomes. The market, the industries, the universe itself inflicts change, as do the people within, and order is impossible to maintain rigidly, so adaptivity and recognising how to manage un-ordered systems is required.

Before this can happen, organisations (and the management thereof!) need to understand how much efficiency and value delivery they will gain from the also-fundamental shifts in their traditional beliefs: it is understandable that organisations wish to impose order and tighten control to make sense, but Dave Snowden warns against the effects of “over-constraining a system that is not naturally constrainable” – you are asking for more inefficiency and problems, not less.

And how exactly does this all fit in with Teaching and Learning?

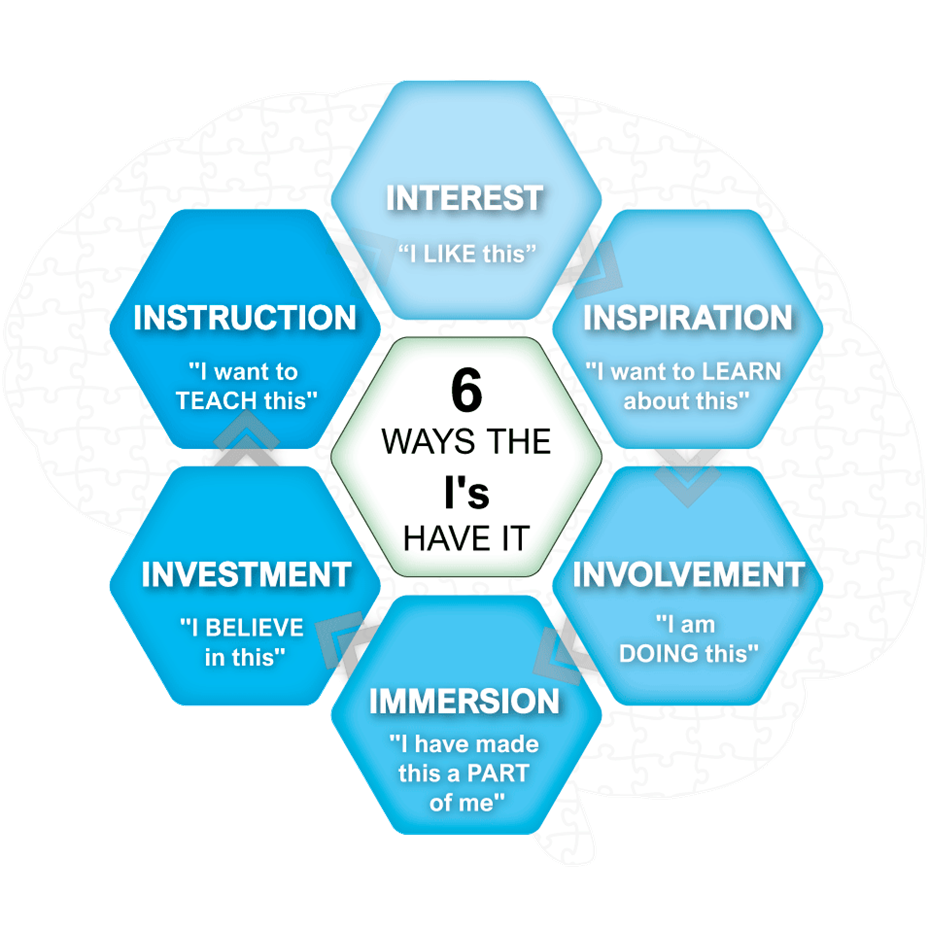

Many of the concepts are relatively new and evolving, and touch on Agile, Lean, Cynefin, and other concepts and frameworks all at once. Teaching these concepts correctly and helping organisations and individuals understand how to learn them effectively (applicably understand them), at the same time as steering away from the temptation to use easy one-size-fits-all fads is therefore key, and the next step in our progress. Understanding of them is blossoming, and now it must be effectively conveyed, used, and put into practice! None of this is any use if it cannot be effectively taught and learned. At the same time, this all fits very neatly into the overall concepts of learning and teaching, which are not by nature ordered and simple.

Equally important is learning when to change. It should not be forced for the sake of change, or without clarity or understanding. Not all change is necessary; it’s knowing when it is and where to start that is crucial, or you could lose opportunities you already have.

Perhaps one of the most important things to teach, and learn, is this: Change is a fact of life, business, and the Universe in general, and it can be feared for good reason; but that should not stop change where change is required or beneficial, or strive to stop change that cannot be stopped. Instead of fearing change, we can teach ourselves to change fear into something more productive: an awareness of grasping opportunities that change will throw up.

You only learn when you are open to change, you move outside your comfort zone, and you accept failure as a lesson that builds success; that uncertainty is the point from which new understanding can grow. The more used to taking that first certain step into uncertainty you get, the less you fear the challenge, and the more you relish it. A good teacher & consultant can help place your feet on that path, and walk the first steps with you.

Sources:

Liz Keogh (lunivore.com)

Katherine Kirk (https://www.linkedin.com/in/ktkirk/)

Dave Snowden (cognitive-edge.com)