The Decisive Patterns of Business

I’ve always been fascinated with patterns. I’ve unknowingly (then knowingly) hunted them for most of my life, choosing to ignore some but embracing others, very often where most people don’t see them. I’ve always sought equations, patterns, an understanding for solving pieces of life instead of relying on the Dei Ex Machina of Survival of the Luckiest and Success without Learning. In this article I’ll delve into the concepts around patterns… and how they affect your business.

Humans naturally seek to create order, find patterns, and build systems. We do this in business, material, social, religious, emotive, physical, and cognitive terms; we seek, create, build, and find comfort in patterns, rituals, methods, which often consciously or subconsciously produce certainty and comfort, and which we use to interpret the world around us.

Patterns are everywhere. We see them all the time, but many of us don’t notice any but the most obvious (although some of us can’t help notice more, and that can be a little overloading at times). But there are many more levels than this – we fall into patterns, and operate on patterns; we think in patterns; our brains operate on primal patterns, too, as do our bodies. We each develop our own patterns at all levels, as well as sharing a common pool.

This isn’t only how we live, operate, and create; it’s also how we decide.

Decisions, Decisions

Humans are a fascinating mixture of instinct, emotion, thought, and rationale. We all contend to greater or lesser extents with confirmation bias, denialism, and the occasional bout of cognitive dissonance, and many of us get stuck on the primary curve of the Dunning-Kruger effect. Some of this is determined by individual brain structure (for example, activity within the amygdala), some by shared structure, some by formative experience.

In short, we are designed to fall into patterns of thinking controlled by impressions, emotions, and filtered, reasoned (and therefore probably inaccurate) past experiences in lieu of fully rationalising using firm facts. This is great for tribalism and building subcultures; it’s impedimentary for accurate decision-making, however, and this can especially affect business.

It has been noted, interestingly, that one group of people consistently can make decisions based more on rationale than immediate patterns, and who tend to see patterns innately, and they are usually autistic (Snowden). So it’s clear that neurodifference changes our processing and allows different capabilities and breakthroughs.

There is some wonderful work done by Dave Snowden of Cognitive Edge on Decision Making, based on work from Klein (1998) around mental patterns and how they affect decisions. In it, he goes very deeply into a lot of the subjects I discuss and consult on which I believe are fundamental – neuroplasticity, engagement, narratives, ethnography, upbringing, and much more.

Patterns for decisions link deeply into Cynefin, Dave’s naturalistic framework for understanding and complexity. Narrative as defined here is far deeper than some consultants who work with storytelling go; storytelling is crucial, of course, but narrative means far more than simple storytelling. It’s context and data, quantification and qualification, discovery and transfer; it’s human cognition and memory, and evolutionary advantage, teacher and student in one linear, often fragmented data flow. All of these fall into patterns.

Decisive Manipulation

Shopping in a supermarket is a great example of pattern-based decisions. From the layout, where fruit and veg is at the front (which alleviates guilt at less healthy foods later), the essentials are often at the far end – forcing us to walk through a veritable cornucopia of delights, most of which leer temptingly at us from the end plinths as “special offers” – the stacking of more expensive products at eye level, and stocking popular combinations next to each other to persuade you to get both, to populating tills with small ‘essentials’ to trigger impulse buying, moving produce periodically, preventing us from going straight to what we want and ensuring we walk past deals we might suddenly think we want. Some stores even play slow music to make us subconsciously spend more time (and money) in the store.

We are literally hacked as we walk into the store, and it’s based on mental patterns – and the manipulation of them for profit.

How often do we really consider a new supermarket purchase based on optimal fit over convenience, attention grab, or mere close approximation?

It isn’t just supermarkets. Casinos are famed for pumping in oxygen, having no clocks, bringing constant free drinks, having no windows, and using the addictive patterns inherent in games and “chance” to attract and hold attention until you have spent every penny you had.

How this affects Leadership (The Decision-Maker’s Quandry)

This is also extremely prominent in business decisions and why they are made, up to and including Director and C-level. Leadership especially falls into patterns because they typically have a set amount of things to decide and carry out which are often similar and repetitive, in less time, with less involvement. This brings the focus away from other areas, and decreases the resolution of patterns behind in a kind of mental bokeh effect (the blurring behind a subject in photography) – they are roughly aware it might exist, but it has zero focus. That this focus is often relied upon to be set by intermediation by management means that things become vastly more complex in terms of interdependency (culture, management style, hierarchy, motivation, and other even more human aspects can all flap “butterfly wings” and have effects on larger things without people realising). Decisions made upon summarised data, which has less context, and is reductionist and interpreted, are likely to produce less than desired results long-term.

Years of experience and understanding can be detrimentally manipulated because the longer we do something a certain way, the less able we are to change patterns or consider things objectively, and the pattern can come to mean more than the data it was designed to react to. When you combine that with a tendency to project on possibly falsely positive outcomes to assuage doubt (this is a firm pattern in many organisations), and the fact that business is changing faster than companies can keep up with, it can present a serious problem (part of the patterns learned are often not to admit there is a problem, of course).

Where things are now changing interestingly alongside the shift in speed of change and focus is that a new generation of Millennials has arisen which has many different patterns to the older, and the older generations in charge of organisations are having real trouble figuring out how to engage them, both as employee and customer. Old ways don’t work so well anymore (the trick is, many never did – they were just good enough at the time).

Modern Business is a perfect example. It works the way it works because it always has, but this happened because it did just enough at the time and chance helped it become “the way of doing things” (more in the blog post Survival of the Luckiest), and therefore a tradition that must be adhered to. Long-term sustainability and equilibrium be damned, new ways are suspicious and “not proven”, and so we remain in base Taylorism-alikes and decision-making that we’ve used for 200 years or more, and is still taught in many business schools, in an accelerating business landscape that no longer supports such an approach.

So how can Leadership realise their patterns?

Gorillas in the Midst

Let’s look at modern pattern examples. There is a great one called The Invisible Gorilla (Simons, Chabris) where you focus on a video of a ball game, only to later discover that a man in a gorilla suit walked through the middle of it without being seen by most people.

Inattentional Blindness is a mental pattern that affects critical decision-making. Survivorship Bias is closely related as well. Professionals are often more likely to fall foul of patterns such as these because of training and practice, unless they’ve been trained to look for what isn’t there (or have oversight).

A further study on the former was done with radiographers, who were shown images where a few frames had a relatively large gorilla superimposed in a section of lung. You can clearly see it, but most of the specialists trained to look for malign lumps missed it, for two main reasons: it didn’t fit the specific pattern they were looking for (despite anything off-normal being important to note), and even if they did, they doubted their own memory or experience after the fact against the experience of others (Reporting Bias and herd behaviour/Groupthink).

These are both also seen constantly in Leadership and Business, where focus on a projected goal is so intense that it’s rarely seen that there can be other, better goals, or that you might not even get to the perfect goal; or too much focus on what a successful company did do (The Secret Shortcuts to Innovation) which may hold no context for your organisation, and not what an unsuccessful one didn’t do.

Understanding the problem

So, let’s sum up some of the most common – and major – Leadership patterns which can stifle business success:

- Assumption of Correlation = Causation

- Simplification/Reductionism for decision-making

- Effects such as the Cobra, Butterfly, and Hawthorne

- Templating or Recipes for easy success or Innovation

- Inattentional Blindness

- Survivorship Bias

- Reporting Bias (conditional mid-process, blame-laying post-failure, rationalising “genius” post-success)

I address many of these individually in other posts, so we’ll just focus on the pattern awareness here.

Leadership can counteract many of these via a paradigm shift into less hierarchical thinking and acceptance of complexity and outlier viewpoints, as well as engaging decent consultants to help frame this in context. This is one reason outside comprehension and coaching is so valuable – the further removed from contextual immersion, the easier it is to see the whole picture. You can learn to see your own patterns, but it takes a release of ego, comfort, and tradition to do so.

Remember: It’s hard to Navigate when you’re too close to the Sun.

Learning this requires understanding why we make these decisions, understanding our own company culture instead of trying to suppress or dress it up, and what Dave Snowden calls “becoming ethnographers to our own condition” to then understand how to sense-make and see new patterns emerge. Of these, some are likely to be best fit, because they emerge and are largely neutral – they were not constructed to fit our preferred patterns, as happens in categorisation.

Some patterns – primal and base patterns – never change, because they’re hardwired. Human patterns for decision making are a first fit not a best fit (Klein, 1998), or in other words, satisfaction, not optimum.

Humans still operate based on a pattern extrapolated from between 5-15% of what our senses take in, consolidated from three things:

| Past Experience | Current Experience | Projected Future Experience |

From these, we create a pattern that is based on a First Fit. As a hypothetical example, back in pre-history this was a distinct advantage; we would fashion a first-fit mental pattern that made us extremely wary when we saw certain patterns which could result in us, for example, dying from predation. Where we then excelled as a species was to adapt our behaviour and exapt our tools, so that we not only moved in groups for defence, and used language in our watch for predators, but divined how they hunted, that spears do more damage than in our hands – and then further, to proactively hunt them to remove the threat rather than simple react as a prey species. These advances became parts of new patterns, and so we progressed.

Intricately bound into this was the formative use of Narrative, alongside a number of other things. We now realise that humans, human intelligence, and interpretation are highly dependent on narrative, as well as a built-in ability to collaborate based on how we engage and learn with each other. The rise of both hyper-complexity in human systems – where they themselves form a meta-complex landscape – and further and further abstraction of thought and learning means that we move ever further from the understanding of how and why we do things, but not from the way we still do them.

I generally see three main ways patterns are used:

- Seeing a pattern set directly as the only likely one in context to a specific situation, fitting perfectly;

- Seeing a number of patterns that can apply and finding the correct one for the situation;

- If one doesn’t exist, try to create a new one, or force the fit of one

But there are other ways we can use patterns, too:

- Sensing patterns as they emerge instead of trying to fit what’s happening into your own preconceived patterns, and applying the most beneficial, even if it changes the projected outcome;

- If no patterns exist, catalyse via actions and then probe patterns as they emerge, discarding negatively impacting ones and applying the most beneficial along with accompanying constraints

The latter are where Complex Adaptive Systems Theory comes into play.

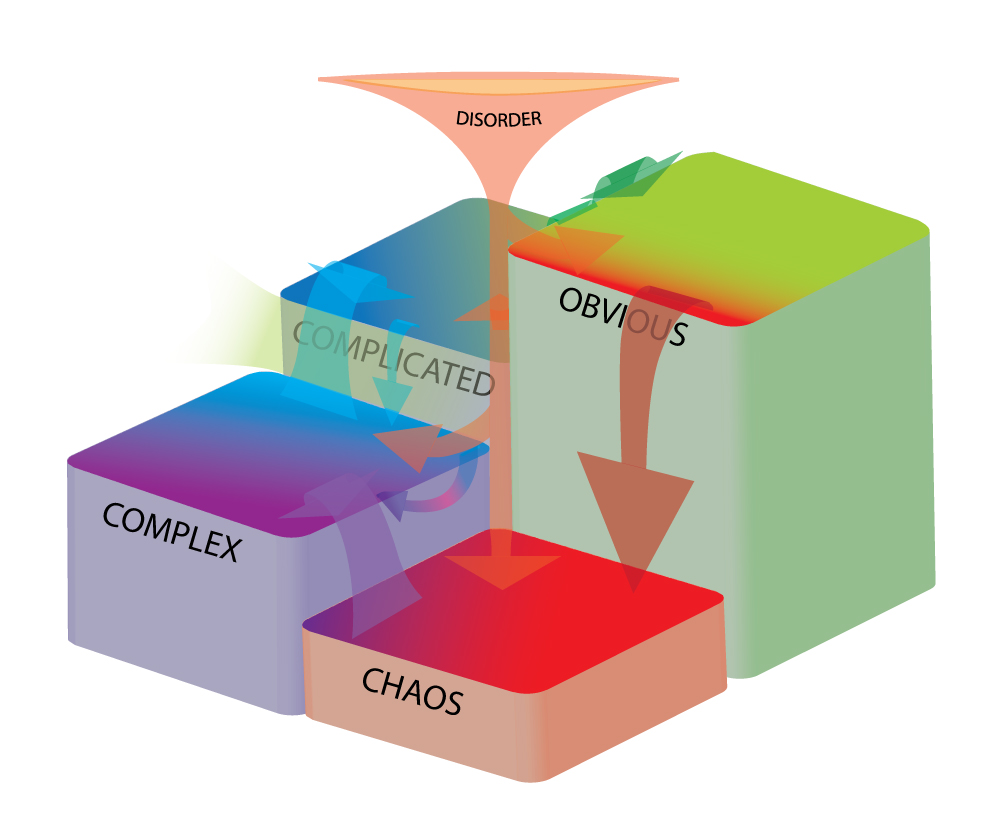

As with nearly everything I do, I end up turning to Cynefin to frame a lot of this, as it’s very deeply bound into my work on human learning, and it helps us understand patterns and why we fall into them. Cynefin as a framework also simultaneously recognises, utilises, and challenges patterns, seeking to help us shift paradigms to new understanding and the finding of coherency in, by, through, and around them (you can learn more about Cynefin in Never Mind the Buzzwords).

It’s not about never using the domains of obviousness and complication, or avoiding Chaos completely, but when to use them; or more appropriately, which situations fall into those domains, and which are complex or chaotic (generally, you know when you’re in the chaotic one). Patterns exist on multiple levels, from instinctive to the highest abstraction, and which domain you are within depends upon the pattern of events – and the context.

I think this is where an interesting misconception inherent to humans comes in around Cynefin. We innately seek to categorise and control situations (which in itself is a pattern), and even a framework such as Cynefin is subject to a certain amount of human attempts to control. Trying to force a situation into a different domain, or pretend that treating it like a different domain will make it become that domain, are unlikely to work. This is because we are still very much slaves to our preconceived patterns and it is comfortable to be able to utilise them.

Situations often dictate you haven’t chosen a domain; the first step is to divine which domain you are REALLY in, and then act appropriately. Just as we often mistake a complex situation for an ordered one, we also can learn about complexity and the ascribe it to every situation, unordered or otherwise. I see a huge number of blogs and consulting manifestos regarding a focus on complexity, and this is a necessary focus, because so much of what we understand is complexity being treated in an ordered fashion, especially human systems. But too much focus on this can be as counterproductive as ignoring it; not everything IS complex, and it’s the flexible and difficult ability to understand where complexity lies vs the other realms and act in context with multi-methodology approaches that allows real transformation.

When you move into a more complex situation such as decision-making within an organisation, in a landscape demanding innovation and disruption, first fit doesn’t serve us quite as well. Pre-conceived notions and old-school management techniques blind us to opportunities and multiple paths forward, as well as innovation, and because patterns and narrative are shaped partially by our past experience, being conditioned by traditions and rigid methodologies and living within that structure day-in, day-out means our first fit patterns may be wildly inaccurate for a complex situation.

If you’re individually or organisationally lucky, you have learned to see this in part and try to decide based on more factors. Sometimes our first feel is good. Often it isn’t, but we have a prevailing cultural dependency on “gut” feel and first impression which can help or hinder in equal measure. That’s going to be down to the context of the situation, but I suspect it’s always worth re-evaluation for a second considered opinion if you can, just to be sure.

Let’s take an HR/Interview example here: the person who doesn’t “first fit” your expectations and traditional interview methods for a role could end up being the optimal fit – but if you stick to your comfortable patterns, you’ll miss the opportunity. It’s worth working on these things and questioning them, as the rituals around hiring are now often hollow and bring less value.

Probing further into Patterns

In my experience, the amount of times a “good” feel or a first decision pays off vs the times it fails is not usually justifiable, but since we retroactively remember and justify decisions as logical rather than unknown or gut-feel assessment, we often don’t recall this (Reporting Bias, as above). This particular pattern makes understanding why we made decisions difficult to investigate.

Patterns and narrative tell us a lot about reality – they are not only useful for the transfer of knowledge, but for discovering context as well. Micro-narratives from multiple sources daily for three months can give us a better idea of a situation than an overarching company narrative for a year, for example, and this allows us to then use quantitative data and support it with qualitative data for context to search for a better-fit pattern. Where our first response might be usually to reinforce company policies and make cuts, swap management teams in to “turn things around”, here we can see a possibility of understanding a root cause instead of trying to treat a symptom (one that is quite contagious for organisations in 2019) and using what is there to understand and repair the situations. This almost always means better understanding, and getting value out of, existing structures, teams, and employees, and is often accompanied by a paradigm shift.

It’s also worth noting that the inherent human use of Narrative is often subject to confirmation bias. Where narrative doesn’t get backed up by credible sources, it can become problematic, because we are designed to believe fragmented narrative, which is fundamental to the evolution of our intelligence. This is, according to research by Dave Snowden (and my own observations), why social media has become such an enabler of serious problems as well as serious advantages – it bypasses what we used to require, which was the contextual, consequential human interaction side, and has removed consequence and accountability from these fragments.

And finally, the manipulation of patterns is well documented in politics, psychopathy, and business alike – but always remember that those doing so also adhere to their own. We’re immersed in a sea of patterns at every level.

Fixing the problem

The first steps to making better business decisions, then, are to be aware of how patterns and narrative both affect us and the systems we create at a fundamental level, and how we use shortcuts and impressions to often make incomplete or inaccurate decisions; to understand that we need to realise the complexity within organisations; and to being able to admit that we can always learn more in context about achieving better value. Mental Kaizen, if you will.

This all links very strongly into finding our humanity again in business, and about having advisers who are not too much part of the process, because they won’t be subject to the same contraints.

The other thing to understand is, outside the ordered areas of our lives (and even eventually within these), patterns do not remain inviolate, because life is subject to change in all areas; nothing is immutable. Like it or not, we must accept that comfort is never forever, and we must dowse new patterns as situations change, allowing them to emerge into understanding rather than trying to hold onto old, less contextual patterns and force new situations into their shape.

So, be mindful that Correlation ≠ Causation; use granular raw data for decision making, not reduced data. Be wary of Cobra, Butterfly, and Hawthorne effects (assumptive patterns). Know you can’t template management techniques or innovation between contexts. Use awareness of complexity to avoid Inattentional Blindness and Survivorship Bias. And be very careful of Reporting Bias.

Find context; get professional understanding from outside your situation; dowse complexity; question your patterns and rationalise your decisions to be optimal. That’s what someone like me is there for; to help understanding of these processes.

We’re creatures of comfort, and patterns comfort us; but we’re also creatures of change. Never stop finding new patterns, learn to leverage them and not be used by them, and you can shift between them and find far more benefit in your business – and in your life.