It is inevitable that, when an industry sees companies struggling to lead, grow or even maintain homeostasis, organisations will shift focus to innovation or disruption. They have to justify continued financial support from investors or parent companies; they have to prove the vision of the CEO is in line with the board’s goals; they have to prove they are providing value to return profit.

We are in an unfamiliar market landscape, populated by a new, populous generation who don’t think, act or engage like the old. Everything is moving faster than ever, and entire sectors (such as retail) are struggling. I’ve spoken about the shift of global economy and the failures of older management styles to keep up in earlier posts, and I’ve also spoken and posted about innovation a lot recently, as it’s becoming ever more a focus as more organisations try to find their footing in the Cycle of Woe, so perhaps now is a good time to explore the current market approach of many companies in more detail and collate my thoughts overall; I’d also like to explore disruption, which I’ve spoken about and worked with before, and I am seeing many more people discussing.

There is a reasonable rule of thumb here:

All Disruptors are Innovators, but not all Innovators are Disruptors.

I think this usually holds true, but not always; sometimes disruption isn’t innovation, but provision of something already needed, existing, and known, but simply not being provided (or that was provided incorrectly and failed). If that need is identified, or a company fails to find a key differentiator or novelty by which to dominate an often saturated market, the focus may shift to disruption in an attempt to change the market itself. Often, a business conflates the two; sometimes, they are both possible at once.

So, let’s explore innovation, disruption, market S-Curves, and more. This is (as usual) by no means conclusive!

A Hot Needle

For many years I worked with an executive named Johan in the IT sector, who at the time headed EMEA. When he came on board, he took the entire area from a dead sales stop to market traction and regained relevancy within ~6 months, which was a phenomenal result, but he didn’t do it by being steady and organic.

Instead, he quite forcefully pushed and demanded, both internally and externally; he made waves, acted quickly, innovated with pricing structures and products that were different and attention-catching, and disrupted people’s expectations and business alike. He didn’t always make friends, but he did make a big difference.

One of his more infamous moments was when he upset a few other players in the market (and I’m sure ruffled a few feathers internally) by publicly announcing that we were going to give the VAR channel “a poke with a hot needle” when the industry least expected it (and due to a lacklustre rebrand, had possibly mis-recognised the company as a potential newcomer).

It was a provocative comment, which had the desired result – people sat up, took notice, argued, laughed, or queried, and the market realised a quite radical shift allowing SME resellers a way into cloud against the larger players, both from the process focus and from new innovations we offered them. It also conveniently spread the rebranded name of the company quickly and re-established the technology as relevant. It wasn’t a total orthodoxy change, but it was a new way of thinking – previously only large providers were offering this type of service, and it caused a great stir in the way the industry was viewed, at least short-term. The disruption process was driven by complementary innovation products. Because of Johan we did, briefly, become a hot needle jabbing at the market, and it reacted.

In a complex/borderline chaotic situation, Johan acted, monitored the feedback, and introduced or re-positioned novel products and offerings. Not everything worked, but it didn’t have to. We picked up on an untapped gap in the EMEA market and enabled smaller companies to compete in the Cloud at the right time – innovation with products, and a relatively quick disruptive shift as a process – in only a few years. Quite an achievement.

It didn’t last, possibly because the company didn’t capitalise on the disruption or gain context from EMEA markets and customers. EMEA wasn’t their core focus, and they didn’t understand it very well; once the company had stabilised, grown, and moved on, it very quickly ossified again, lost a lot of impetus, and methodology became as or more important than results. The Cycle of Woe began again (without Johan, myself, and a number of other people, who had moved to other things). Even a jab like that can be quickly forgotten.

Working with Johan was an interesting experience – we didn’t always agree, but we respected each other’s specialities, and I don’t think either of us would argue with the results we were individually getting. He certainly could be a hot needle (and I’m sure still is!).

Types of Innovation

Innovation is often automatically associated with a product. Whilst of course this can apply to services (Spotify is a hybrid example), it’s still essentially a brand.

Many professionals categorise innovation into 3 areas:

| Incremental |

Definitive |

Breakthrough |

There are purists who will insist that true innovation can only be “Breakthrough”, but innovation isn’t necessarily only world-shattering and huge, so I don’t agree with this. It is, however, what most people mean when they speak about innovation as a buzzword: a differentiator that is a breakthrough to success.

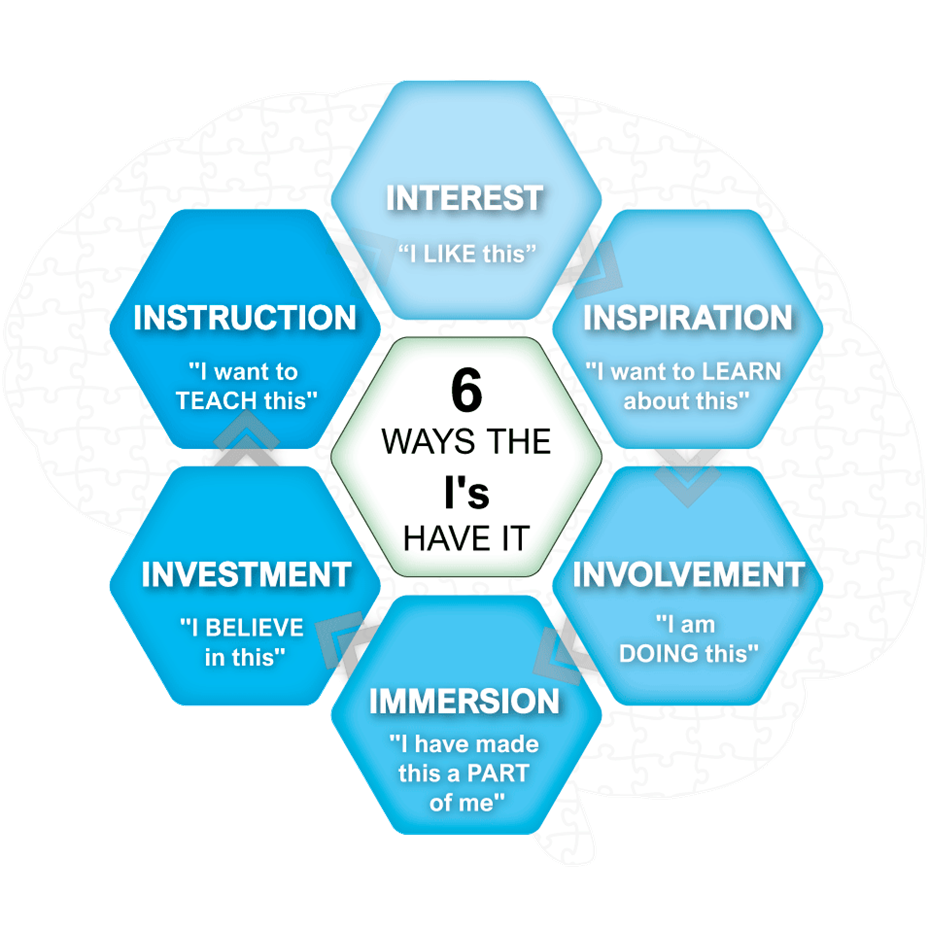

I have found that innovation as a concept also tends to be subconsciously considered in two other ways:

| Being Innovative |

Innovating |

The first is often a goal in and of itself. I’ve attended many companies where they are desperate to differentiate, to become a market leader with any product; they want novelty, and work towards it without direction. It doesn’t matter what it is, just that they do it. It’s an outcome; a badge of worth.

The second is a pathway on a journey that is a coherent, contextual path forward, where they innovate with a product at the core of the business. It’s a part of the process of value delivery; whilst being an achievement, it is an enabler, part of the overall narrative.

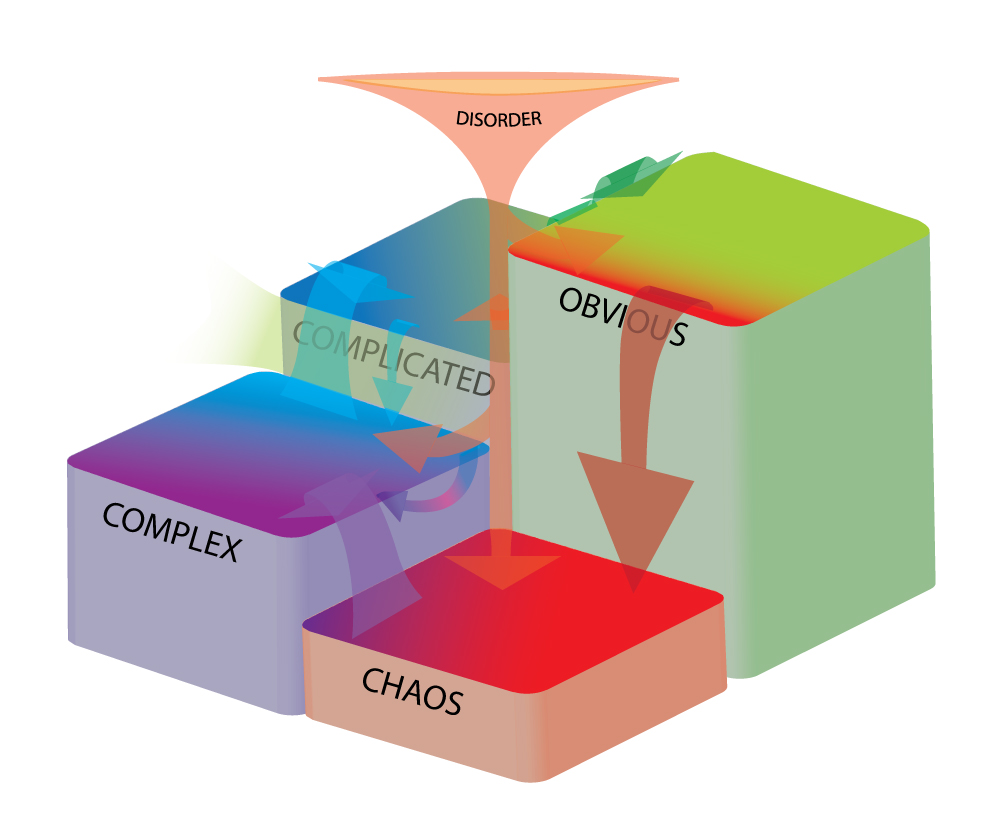

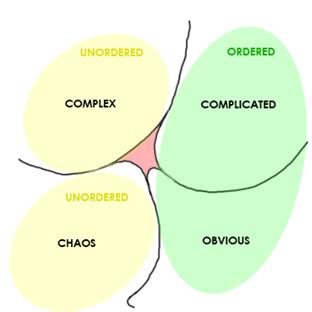

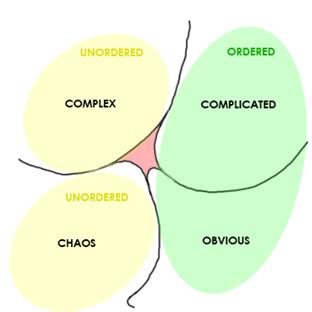

I’ve posted plenty about Cynefin in this blog, but as a quick summary in terms of innovation, the main domains all have their place. Because of this I distinguish four types of innovation, not three:

The Cynefin Model showing Order/Unorder, with Disorder in the Centre. All rights reserved Cognitive Edge

Incremental Innovation happens in the nicely ordered, rigid, boring, safe space of Obvious, where all works as expected and predicted, and if innovation happens at all, it’s in small, by-the-numbers ways (often debatably innovative, often borderline nice-to-have).

Definitive Innovation happens in the governed, ordered, expertise-driven space of Complication, where all works as expected and predicted but the rules are looser to allow for multiple causes and effects, via key differentiators – stand-out features that not every product has.

Breakthrough or Radical Innovation occurs in the unknown, unordered, dispositional and uncertain space of Complexity, where we can only say what is likely to happen, and there is no clear cause and effect. All we know is that any changes will effect everything, and could be good or bad. It will likely be both serendipitous and unexpected, and often is game-changing both in terms of value delivery and direction. More organisations than you’d think are here.

Disruptive Innovation lies amidst the total unorder and crisis of Chaos where everything is, well, PFU. A very bad place to be – we don’t know what is likely to happen, what is happening, or what we can do, only that we MUST do something. We act or die, essentially. Innovation that occurs here is make or break – if it works it will not only help manage the crisis and differentiate the company, but is likely to be so novel it disrupts entire markets. There is a crossover with Radical innovation here, as chaos can be used as a guarded area to spark disruptive innovation in relative safety using safe-to-fail probes.

It is important to innovate in context, but a vast majority of companies are in Disorder, that red spot in the middle; that is, they believe they are in a specific domain when in fact they are not. This usually errs on the side of believing themselves in very ordered situations when they are in very complex situations, but that is not always the case; the key is that they aren’t where they think they are (or should be). Unless you are extremely lucky, making strategic decisions or trying for innovation here will likely be unproductive or damaging based on a lack of real-world context. Randomness generally lacks coherency; emergence doesn’t necessarily.

So, to summarise: Innovation is change/novelty of varying types, and it can be mild or extremely disruptive.

Types of Disruption

When we talk about market disruption, we may mean something that is not necessarily innovative, but may be so required in a market it gets widely adopted enough to become the new orthodoxy. This can happen in such a subtle fashion that it may not be realised until after the fact, unlike innovation, which relies on being extremely visible to spark things like The Hawthorne Effect, i.e. humanity’s interest and adoptive reactions to novelty.

Disruption can include:

New Market Disruption – Targeting a market where needs are not being met by existing dominant orthodoxies

Low-End Market Disruption – Targeting a market where not all features offered by existing dominant orthodoxies are valued, except by high-end customers

Innovative Disruption – A process where in the short-term a new market is created and grown based on a product or service, and in the long-term finally displaces an existing market

Market disruption is often not a fast process, unless the gaps in the market are crying out for it. It often happens through general adoption over time – thus, a subtle ubiquity – rather than early adoption, “the next big thing”, and ambassadorial representation. It’s perhaps better thought of as a displacement rather than a spearhead. Kickstarter is a great example of tons of innovation which clearly doesn’t disrupt entire markets immediately, or even at all.

There is also another type of disruption which is a result very often of innovation and market disruption, that isn’t often considered by organisations, and which needs to be understood, and that is role disruption – the effect where changes and progression in the marketplace, new technologies, and paradigm shifts all contribute to previous roles no longer being required or substantially changed. This matters, especially to individuals in an ecosystem.

There will be new roles in this Brave New World, of course – for example, automation doesn’t automatically equal removal of humans, often a shift in their expertise and role, or an opportunity to learn new skills – but a lot of change is coming, and has come before. This is especially of concern to the current largest generation – who are no longer Baby Boomers but Millennials – because they face less security, more uncertainty, and more difficulty by a considerable amount than the previous generation.

Role disruption, and the concern over role disruption, can have a number of knock-on effects that need to be addressed by culture, learning, and realistically projected prospects rather than the age-old adherence to inaccurately modelled outcome-based measures and falsely-positive forecasts – some of this was covered in The Red Pill of Management Science.

So to summarise: disruption can occur at the market, the company, or the role level, and is a process, not a product, affecting ubiquity.

The conflation of Novelty and Displacement

One thing I find interesting is how many businesses seem to conflate the two concepts, as there is a lot of crossover between the two approaches, which muddies execution. Both of these things represent stages of paradigm shift, and although they often occur independently, they can occur together as well. For example:

When someone says “smartphone”, what phone do you think of?

Chances are it’s an iPhone. It was first to define the form factor as the first true multi-functional smartphone (in the current long-term form), and hasn’t significantly changed since that incredible step forward (past incrementally innovating).

Apple used an incredibly clever and aggressive marketing strategy to make this product unspeakably novel, desirable, functional, and elite. It worked. Everyone who was anyone wanted one. The drawbacks, of which many still exist today, simply didn’t matter.

What’s interesting is that the i stood for two things: individuality, and internet (given everyone then seemed to have one, I consequently also decided it stood for irony). A subtle message which worked; iPhones became the de facto communications device.

Apple managed the rare feat of both innovating AND utterly disrupting the market very quickly. This happened because the market was at a point of orthodoxy change, and it was the exact right time to become the new paradigm, shifting Microsoft’s Apex Predator dominance of software to a new orthodoxy of software and hardware combined in the form of an object of material desire, which not only enhanced functionality and ability for users, but also image and self-worth.

This ubiquity came from incredible brand awareness, and a melding of the OS and hardware into one product. There is only one “iPhone”, which merely manifests in different forms.

However, these drawbacks (high price, poor non-Apple integration, availability, lack of customisation, fragility (especially of screen), constantly changing power adapters, slowdown over time, lack of memory card, sealed battery, requirement for costly Apple store for many minor issues, punitive action for jailbreaking), although intially ignored, became better understood, and slowly the market began to change. Dominance shifted, market presence shifted.

This was due to Android. The first cellphone running it was released a year after the iPhone (the HTC Dream G1), but the OS had actually preceded the iPhones’ – it just hadn’t yet been refined or named.

Android phone manufacturers didn’t particularly innovate, certainly at first; they simply allowed more people the chance to do more, for less, to belong, and they spread, quietly. A much wider range of devices filling the gaps in the market were developed; different combinations of hardware, price point, customisation, and the adoption of a universal charging standard, as well as memory expansions, battery changes, variety of materials, and so forth. People who couldn’t or wouldn’t buy an iPhone took up the diverse legions of Android phones instead, and discovered in many cases they were more capable, less restrictive, and mostly affordable, if not as smooth or elite. With the sheer variety of OS customisation and hardware options, Android phones became far more individualised than iPhones. A plethora of companies sprang up; where they couldn’t compete with the desirability – apart from companies such as Samsung – they competed by offering a piece of the smartphone pie.

Looking at the % of smartphone market share by OS, we see this:

As always happens with orthodoxies, once they become widely adopted they are no longer disruptive, or innovative in anything more than small increments. The slow disruption of Android has told over time; iPhone OS phones are still mostly the poster-phone for smartphones, but they are now so omnipresent in consumer consciousness that there is no more novelty. They hold perhaps 23% of the platform market, impressive for one company.

Meanwhile, Android-based phones in their extreme variety hold nearly 75%. They slowly but surely disrupted the market, and became the new norm.

If we then look at smartphone manufacturer market share %, you might expect Apple to be the top of the tree based on the above, but we find:

So when you think “smartphone”, you may think iPhone first through conditioning – but now you also might instead think Samsung, which has gained a larger market share than the original innovative disruptor. And, with a huge presence in Asia and now the west as well as definitive innovations, Huawei is becoming a new name to recognise. The smartphone market is also due a huge upheaval, which is likely to come from foldable screens – which Huawei, again, seems to be at the forefront of.

It is important to remember that innovation doesn’t automatically equal disruption, and that they can be independent or happen together, but they WILL happen. The one constant in business is that change is inevitable – which is why rigid, dominant paradigms eventually fall foul of complacency.

Orthodoxies, Paradigms, and Apex Predators

So where does this change occur?

There are a number of places disruptive paradigm shifts and innovation can happen more easily, and a couple where it MUST happen or dire consequences will be faced. I won’t go too deep in this post, but there are several things to be aware of here: the market arranges itself around the Apex Predators, there is a lifecycle to all orthodoxies, and (as ever) context is crucial.

Market Lifecycles

Many people are familiar with the basic market lifecycle, and indeed this is typically used in strategy because of the assumption that you always start with a “green field”, or a standard approach.

But this does not take context into account, which is critical, especially for innovation and disruption to work. You very rarely start from a green field. A more realistic version is Moore’s “Crossing the Chasm” depiction:

Which shows the chasm which must be crossed. Failing here means you never become relevant; crossing means you will see a drastic shift in focus.

It is important to note that many companies do not cross this chasm. Using Kickstarter as an example again, innovation is wildly high and wonderful, but only 36% of companies reach successful funding. The actual % of companies that go on to become a force or even a long-term blip in the market is much lower than that. Very few end up disruptors.

84% of the top projects ship late; many of them find resource problems, even liquidate soon after creating the successfully funded product. Creating a stable, profitable company afterwards requires other funding and skills (Angel, Venture, etc) and a continuous value delivery stream. If the whole company is based on one innovative product, and people quickly lose attraction to novelty, and that’s all you had, you’re dead in the water.

A key shift here is from Sell to Make to Make to Sell. Leadership often assume or require that initial early adopter sales will continue linearly, and they don’t. A decline in sales usually leads to reduced funding, lost confidence, and not enough push to get across the chasm. Innovation is not a guarantee of success; market disruption is not a guarantee of success.

So, how do we introduce radically new, innovative products on the other side of the chasm?

S-Curves

One method is to add novelty to what people already know they want; the desire for novelty then crosses the chasm because it becomes, for a time, more important than the product. This sparks mass uptake and desire for the product which breaches the gap; this is definitive innovation from Complication.

Markets are constantly in flux with this behaviour; phone cameras are a good example. All phones have them, and they have gone from being ignored to being used constantly for everything from selfies to business receipts.

Huawei’s standout features on their P20 Pro flagship (at the time) were the triple lens camera that delivers incredible pictures that still blow many other phones – iPhone included – out of the water, an insane battery life, and an eye-catching 2-tone twilight colour reminiscent of the old TVRs. A smartphone is a smartphone – but this differentiated them enough to lead to a huge surge in Huawei sales in the west (which continued until the recent widely-broadcast concerns about the technology and security, which consequently have led to a current decline). It didn’t hurt that they had less reports of batteries exploding than the two leaders, either. The novelty told: P20 Pros became more desirable than Samsungs or iPhones for many people within the last 2 years.

So how we achieve this symbiosis? How do we innovate and disrupt at the opportune point?

The best way is to divine a point where the dominant way to do things is becoming commodified or coming to an end, whether it’s known or not by most players, and find space for novelty or a regime change. This can be additional innovation alongside the orthodoxy, radical or disruptive emergent innovation at the right point, or you may be able to alter the course of the whole paradigm akin to switching a train onto alternative tracks via the subtle spread of process (i.e. disrupt the whole market).

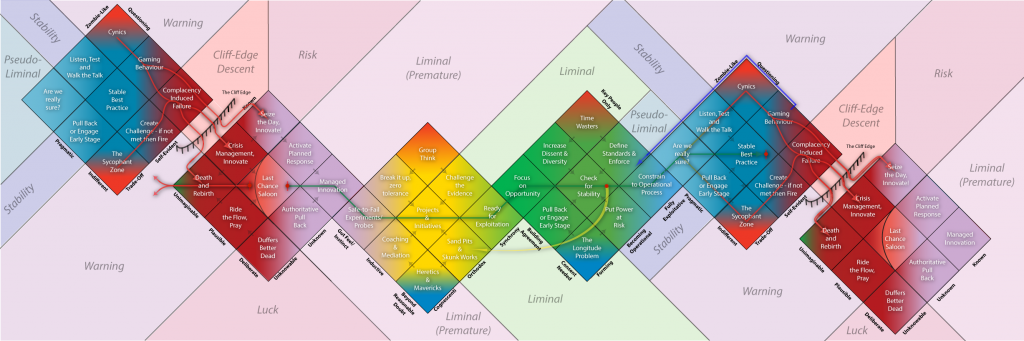

One way to view this is to look at an extension and expansion of the Gartner Hype Cycle:

Credit goes to Dave Snowden of Cognitive Edge, who pioneered the linking of the curves, theories and applications.

I’ll discuss S-curves another time, but here we can see a narrative of the relevance to novelty and the hype-cycle at the lower left, and the subsequent establishment of orthodoxy to create Apex Predators within a market. This leads to the eventual beginning of commodification and complacency by the Apex Predators due to being too invested and effective over time. Think of past extinctions caused by becoming a food-chain dependent megapredator that is too specialised, and you’re not far off.

The two key decision making points for understanding where change can integrate with the adoption curve will be reached: the pre-chasm point where weak signals tell you there are opportunities to be explored, and the end-chasm point where you have fallen in, unseeing, and must change to climb back out. If these are ignored, the fall or irrelevancy of an Apex Predator causes a trophic cascade (the radical reshifting of the entire ecosystem, which tend to be defined by Apex Predators).

Meanwhile, the point of “crossing the chasm” and uptake either via disruption, novelty, or both – in context and at the right moment – leads to the rise of new Apex Predators and/or the effects of total market disruption.

There is a lot more to this than that of course, and this doesn’t explain how it fits into Cynefin or other frameworks.

It’s not enough to be innovative; you can have the best product on the market. It’s not even enough to be disruptive; you can infiltrate the market at the low end and spread your net. It’s also about weak signal detection and uptake moments. It’s certainly not about being currently dominant, as that means you are more likely to be blinded to threats.

A last thought here: people (especially in mid-tier management in my experience) often choose moderate quality/profit using known contacts over potentially high quality/profit with new contacts, because it’s safe and hithertofore guaranteed. Or, to put it more succinctly, they will often choose certainty over uncertainty, especially in the context of an uncertain, unknown, changing market situation.

Shake-ups

From time to time, every market needs a shake-up, as does every company, preferably not through situations such as the Cycle of Woe. This is what Cynefin and safe-to-fail probes can be used for; to find a new path and avoid complacency before it becomes an issue.

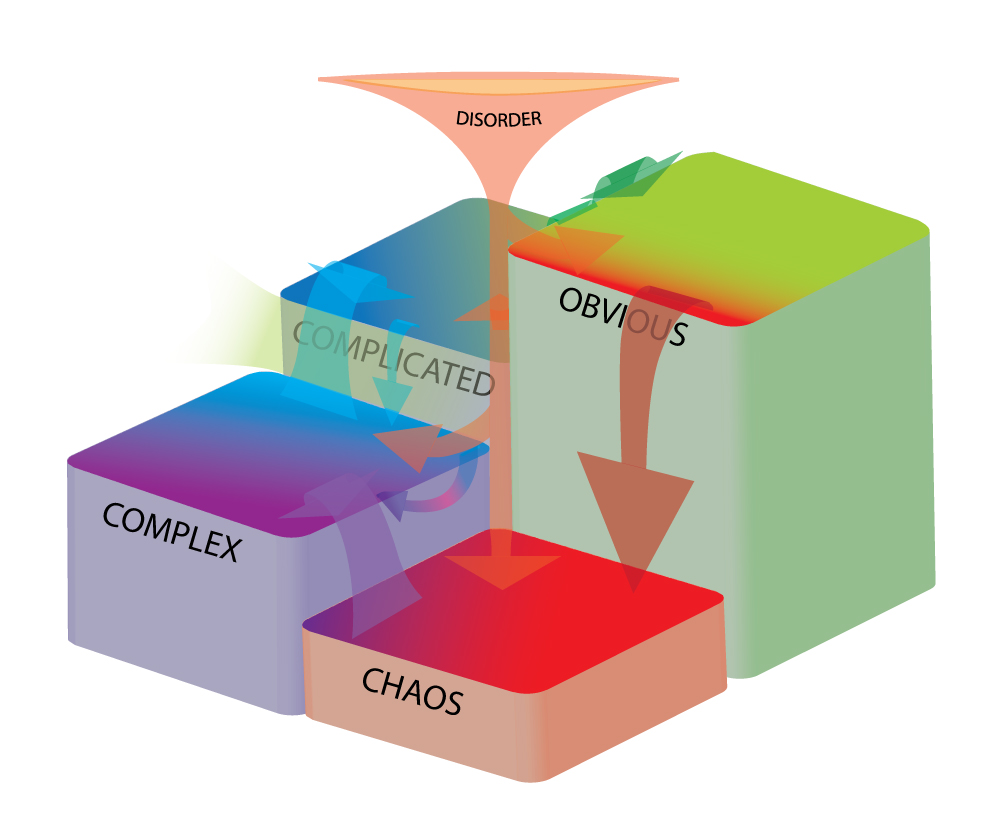

Complacency induces failure, eventually, and this is a real problem, because that failure is often catastrophic. Dave Snowden likens this to falling from a cliff-edge, and when you understand how Cynefin allows you to make sense of scenarios, and how strategic and tactical complacency is widespread and usually unnoticed ESPECIALLY to Apex Predators, you realise this is a very apt analogy.

A firm that is complacent is at great risk of falling off that cliff-edge because someone else’s disruptive innovation has abruptly made them obsolete, which makes it very hard to re-establish coherency again (many companies here end up in death/rebirth unless they can secure new funding or benefactor). Bigger dominant organisations are often more complacent by nature, and the bigger you are, the harder you really can fall.

The long fall from Obvious to Chaos through Complacency-Induced Failure

Old giants rarely die; they can become too big for mortality. IBM is still a powerhouse; Microsoft is still gigantic. But with the shift of market and paradigm, the Big 4 in tech today are considered to be Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon. Occasionally Microsoft joins the club as a fifth member who has some form of tenure – for how long, we don’t know.

If you look at these main examples, which of them are still both innovating and disrupting?

Understanding how to innovate and/or disrupt in context and emergently is vital for companies of any size, arguably more so the bigger they are; being able to see when you can or must do so is equally critical. They must furthermore understand how to do it in this new emergent, uncertain market landscape we’ve never been in before, for an entirely new generation. It’s become much harder to do.

Get it wrong, and you’re strolling near that cliff edge… while you’re looking the other way.